By Bradley A. Huebner

Growing up in Levittown outside of northeast Philadelphia, Charles “Chic” Hess remembers the sports pages containing stories and footnotes about the famed Wonder Teams from Passaic, N.J. Professor Ernest L. Blood, Passaic’s head coach, had learned the game from its inventor, James Naismith. Blood extended his physical training supervisor duties to include coaching basketball early in the 20th century.

Like Naismith, Blood endeavored on a career keeping Americans physically fit. In the winter, that meant playing the new game, basket ball.

Hess played the game and later coached it in college and high school, making an imprint on the sport. When he heard people refer to another Naismith disciple, Forrest “Phog” Allen of Kansas as the “Father of Basketball Coaching,” he felt it slighted Blood’s exploits.

“Blood won 400 games before Phog Allen won his first,” Hess said.

Dr. Professor Blood’s teams used press, passing offense to humble high school, college teams in Dr. ‘Chic’ Hess’s book about a Naismith disciple

Edit Image

By Bradley A. Huebner

Growing up in Levittown outside of northeast Philadelphia, Charles “Chic” Hess remembers the sports pages containing stories and footnotes about the famed Wonder Teams from Passaic, N.J. Professor Ernest L. Blood, Passaic’s head coach, had learned the game from its inventor, James Naismith. Blood extended his physical training supervisor duties to include coaching basketball early in the 20th century.

Like Naismith, Blood endeavored on a career keeping Americans physically fit. In the winter, that meant playing the new game, basket ball.

Hess played the game and later coached it in college and high school, making an imprint on the sport. When he heard people refer to another Naismith disciple, Forrest “Phog” Allen of Kansas as the “Father of Basketball Coaching,” he felt it slighted Blood’s exploits.

“Blood won 400 games before Phog Allen won his first,” Hess said.

Edit Image

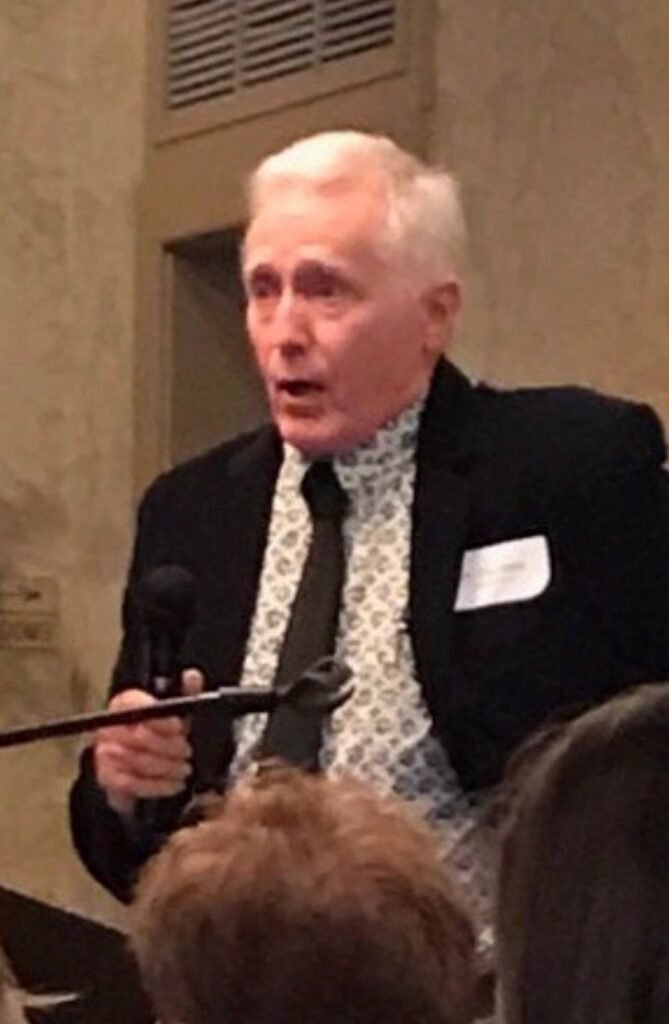

Dr. Chic Hess gives a speech about Professor Blood. Photo courtesy of Hess.

In the 401-page hardcover that Dr. Hess wrote to honor Blood and to publicize his team’s achievements, he captures the career of the “gray thatched wizard” whose teams won 159-straight games at Passaic High School. That came after Blood’s perfect first coaching job at Potsdam Normal School 60 miles from Passaic where he started with 100 straight wins.

Blood utilized a fast passing game that allowed the “ball to do the work”. He tasked his boys to take on junior colleges and other college teams.

Meticulously researched, the story details each game during Blood’s winning streak at Passaic from Dec. 17, 1919, to Feb. 26, 1925, when the boys from Hackensack secured a 39-35 victory to halt the dominance. The Passaic Daily News put it simply in a three-word banner headline:

PASSAIC HIGH LOSES

Hess, who earned his doctorate from Brigham Young University in athletic administration, devoted countless hours researching the topic.

During his graduate school days, Hess spent chunks of two summers in Passaic trying to nail down just how this unbeatable coach never seemed to taste defeat. Eventually the local library gifted him with his own key to stay late.

“I got in touch with many of the children of these players,” he said. “Two summers in a row I spent a couple weeks or more in the Passaic library and looking through the microfiche and interviewing of some 90-year-old people.”

To capture the feel and to visualize the emotions of many of Passaic’s games, Hess walked through the Paterson Armory, where Passaic moved its games after crowds in the thousands couldn’t squeeze into the high school gym. A fire in the Paterson Armory in 2015 hastened the destruction of that historic site, unfortunately.

The nonfiction book also veers into the political climate at Passaic, where the principal and school board battled Blood for popularity and control. Blood never wanted his players to be at a disadvantage, so he fought to get the referees he wanted–or rather, to avoid those he didn’t trust–and to play in neutral sites for big games, if not near his hometown.

He also battled his administration in the public eye. Blood lived a principled life and oppose any treatment he felt unjust, the kind of bravado that often results in a coach’s dismissal, something the administrators would have preferred if not for Blood’s widespread community support.

Understanding the need to entertain fans between America’s involvement in two world wars, Blood brought Zep the Bear to games, sometimes sharing space in a taxi en route to the armory. While the bear was young and manageable, Blood’s son Paul or someone else would wrestle the bear on game nights.

Records and statistics didn’t always match up as Hess compared game notes from different newspapers. He pared down the data to find the proper final tallies.

He also secured primary sources like original memos and hand-written correspondence between Blood and the Passaic administrators. Which one provided the greater challenge–locating personal missives or inferring the correct basketball data–is open for debate.

“I’d get two or three different versions of each game,” he said. “Once I absorbed everything about a game or a period of time, I’d say, ‘OK, I can see it, and then I’d write it.'”

In his quest to properly capture America’s first celebrity coach, Hess consulted an expert. Living in Hawaii, he had a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer nearby.

Retired professor and biographer Leon Edel, a 1963 Pulitzer Prize-winning writer who’d written about literary icon James Joyce, penned a five-volume biography on Joyce and another on writer Henry James before dying at 89 in Honolulu.

Hess examined Edel’s book Writing Lives and Telling Lives inspired Hess’s quest to relate Prof. Blood’s life. He tracked Edel down through the phone book and acquired more advice to help reveal Blood.

“He said, ‘Tell your story,'” Hess said. “‘It’s your story. Know your material. And don’t use too many quotes.'”

As he pieced together countless facts, anecdotes and even a few quotes, Hess discovered his writing voice.

“The research for the book continued from Utah years up until I started writing in 2010,” he said. “The book was published in about 2013.”

It made him a published author and an official basketball historian. With his credentials as the valedictorian of his class at Brigham Young, where he earned his doctorate degree with an A average, Hess has become not only a revered scholar, but a basketball authority.

All that’s left is to see Prof. Blood and his bear and the Wonder Teams on the big screen. Hess said he wrote 80 pages of a screenplay, which he’s turned over to others to finish. The movie would be a “Hoosiers” for the Jazz Age.

Blood would be the embattled coach fighting off demanding school board members while taking his teams to lofty heights. And Hess would be a septogenarian with a new mass appeal.

Chic Hess gives a speech about Professor Blood. Photo courtesy of Hess.

In the 401-page hardcover that Dr. Hess wrote to honor Blood and to publicize his team’s achievements, he captures the career of the “gray thatched wizard” whose teams won 159-straight games at Passaic High School. That came after Blood’s perfect first coaching job at Potsdam Normal School 60 miles from Passaic where he started with 100 straight wins.

Blood utilized a fast passing game that allowed the “ball to do the work”. He tasked his boys to take on junior colleges and other college teams.

Meticulously researched, the story details each game during Blood’s winning streak at Passaic from Dec. 17, 1919, to Feb. 26, 1925, when the boys from Hackensack secured a 39-35 victory to halt the dominance. The Passaic Daily News put it simply in a three-word banner headline:

PASSAIC HIGH LOSES

Hess, who earned his doctorate from Brigham Young University in athletic administration, devoted countless hours researching the topic.

During his graduate school days, Hess spent chunks of two summers in Passaic trying to nail down just how this unbeatable coach never seemed to taste defeat. Eventually the local library gifted him with his own key to stay late.

“I got in touch with many of the children of these players,” he said. “Two summers in a row I spent a couple weeks or more in the Passaic library and looking through the microfiche and interviewing of some 90-year-old people.”

To capture the feel and to visualize the emotions of many of Passaic’s games, Hess walked through the Paterson Armory, where Passaic moved its games after crowds in the thousands couldn’t squeeze into the high school gym. A fire in the Paterson Armory in 2015 hastened the destruction of that historic site, unfortunately.

The nonfiction book also veers into the political climate at Passaic, where the principal and school board battled Blood for popularity and control. Blood never wanted his players to be at a disadvantage, so he fought to get the referees he wanted–or rather, to avoid those he didn’t trust–and to play in neutral sites for big games, if not near his hometown.

He also battled his administration in the public eye. Blood lived a principled life and oppose any treatment he felt unjust, the kind of bravado that often results in a coach’s dismissal, something the administrators would have preferred if not for Blood’s widespread community support.

Understanding the need to entertain fans between America’s involvement in two world wars, Blood brought Zep the Bear to games, sometimes sharing space in a taxi en route to the armory. While the bear was young and manageable, Blood’s son Paul or someone else would wrestle the bear on game nights.

Records and statistics didn’t always match up as Hess compared game notes from different newspapers. He pared down the data to find the proper final tallies.

He also secured primary sources like original memos and hand-written correspondence between Blood and the Passaic administrators. Which one provided the greater challenge–locating personal missives or inferring the correct basketball data–is open for debate.

“I’d get two or three different versions of each game,” he said. “Once I absorbed everything about a game or a period of time, I’d say, ‘OK, I can see it, and then I’d write it.'”

In his quest to properly capture America’s first celebrity coach, Hess consulted an expert. Living in Hawaii, he had a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer nearby.

Retired professor and biographer Leon Edel, a 1963 Pulitzer Prize-winning writer who’d written about literary icon James Joyce, penned a five-volume biography on Joyce and another on writer Henry James before dying at 89 in Honolulu.

Hess examined Edel’s book Writing Lives and Telling Lives inspired Hess’s quest to relate Prof. Blood’s life. He tracked Edel down through the phone book and acquired more advice to help reveal Blood.

“He said, ‘Tell your story,'” Hess said. “‘It’s your story. Know your material. And don’t use too many quotes.'”

As he pieced together countless facts, anecdotes and even a few quotes, Hess discovered his writing voice.

“The research for the book continued from Utah years up until I started writing in 2010,” he said. “The book was published in about 2013.”

It made him a published author and an official basketball historian. With his credentials as the valedictorian of his class at Brigham Young, where he earned his doctorate degree with an A average, Hess has become not only a revered scholar, but a basketball authority.

All that’s left is to see Prof. Blood and his bear and the Wonder Teams on the big screen. Hess said he wrote 80 pages of a screenplay, which he’s turned over to others to finish. The movie would be a “Hoosiers” for the Jazz Age.

Blood would be the embattled coach fighting off demanding school board members while taking his teams to lofty heights. And Hess would be a septogenarian with a new mass appeal.