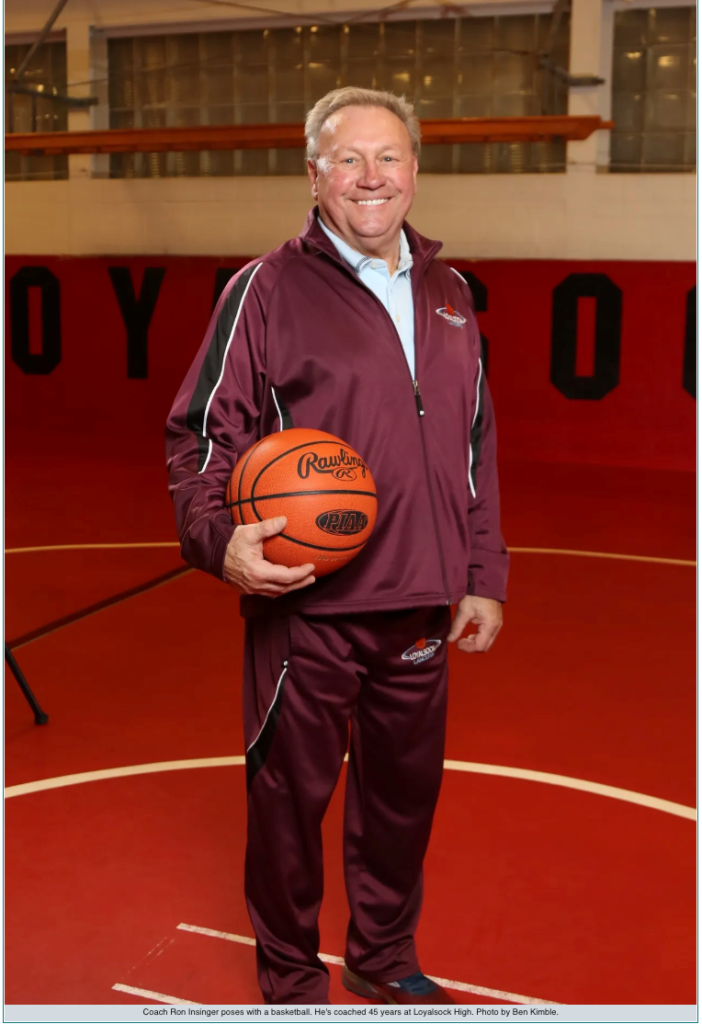

Coach Ron Insinger poses with a basketball. He’s coached 45 years at Loyalsock High. Photo by Ben Kimble.

Coach Ron Insinger poses with a basketball. He’s coached 45 years at Loyalsock High. Photo by Ben Kimble.

Loyalsock High had four coaches when the school started competing in basketball over half a century ago, before Ron Insinger accepted the head boys job in 1974 at age 22. None of those early coaches stayed longer than four seasons.

You couldn’t blame Chic Hess for leaving after only two seasons. He migrated to Lebanon High where he’d coach the great Sam Bowie.

In Insinger’s third season, his career abruptly ended. He officially resigned after a family tragedy floored Ron and wife Carol, his former high-school sweetheart. Their 28-month-old first child–Ronald Scotty–took sick on the second day of basketball season.

“He was in perfect health,” Coach Insinger recalled. “Never sick, never anything. He woke up with an ear ache.”

Doctors flew him to Geisinger Hospital in Danville for immediate care. Coach Insinger said he only got four hours with his boy before he passed. Spinal meningitis.

“There’s nothing worse than burying your son,” said Insinger.

Actually, there was. Three days later one of the boys on Ron’s junior varsity team was killed on the way home from a Saturday practice.

“He was T-boned in a car accident,” Ron said.

The combination of tragedies the first week of the season prompted Ron to consider stepping down. Who could blame him?

“I did quit,” he said, “but the players wouldn’t let me.”

Farmers don’t quit. They don’t even take days off. Survival depends upon rising and completing the chores, milking the cows, which Insinger did at 5 a.m. every morning. About 100 cows on their 225 acres. After school he attended practice for either football, basketball or baseball. At night he completed the second round of chores on the farm.

Ron and Carol would have two daughters, Laurie, 40, and Lisa, 36. The Good Lord didn’t bless him with another son. He blessed him with nearly half a century of them.

“I have the mentality that the boys on my team are my sons,” he said. “They’re in my office a couple times a day. It gives me a reason to get up on the morning. I do indeed love my players, and I tell them that every day.”

Insinger’s daily wakings reciprocate that motivation, as he gives his players an extra reason to come to school. Now in his 45th season coaching Class 3A basketball at Loyalsock High in Pennsylvania, Insinger is the winningest coach in state history with a record of 1,014-232.

Nationwide, there are “fewer than 40” high school coaches with over 1,000 career victories. DeMatha legend Morgan Wootten (1,274-192) is one. He’s in the basketball hall of fame in Springfield, Mass. Bob Hurley (1,184 wins) is another. He’s also in the hall.

Insinger ranks just ahead of St. Joe’s Prep coach William “Speedy” Morris, who secured most of his victories at LaSalle University and Roman Catholic High in Philadelphia before taking over The Prep.

Insinger, Loyalsock’s athletic director since 2009, has won 38 league titles and 22 District 4 titles employing a system he’d learned from legendary UCLA coach John Wooden. This past season his Lancers went 27-2, end their season for the 14th straight year to a non-boundary school in the PIAA playoffs.

He’s a hall of fame coach and multi-million dollar entrepeneur whose gymnasium bear his name: Ron “CI” Insinger. CI stands for Coach Insinger.

“People know me more by CI than Ron,” he said.

IN THE BEGINNING …

Insinger’s only losing season in 45 years came in 2000. His winning results harken back to John Wooden’s UCLA dynasty because that’s who selected Insinger to join him for lunch back when Insinger was starting out in coaching, following a career playing point guard at Lock Haven University’s JV team.

Edit Image

“My first fall I went to a coaching clinic in Cherry Hill, New Jersey,” Insinger recalls. “I was walking around during a break and John Wooden took me by the arm and said, “Are you lost?”

I said, “I sure am.”

He said, “How about having lunch with me?”

Insinger sponged as much wisdom as he could off the greatest coach of the 20th century while scarfing cheeseburgers and fries at the Hyatt House restaurant. He built his program on Wooden’s famed Pyramid of Success.

“We built our program on toughness, trust, togetherness,” Insinger said. “We molded it after Wooden’s philosophy of success.”

Edit Image

Adhering to teaching the fundamentals and drilling to enhance skills connects the two coaches as much as anything. Insinger puts his best coaches at the youth level so his future players learn the game the right way from the outset.

They learn man-to-man defensive fundamentals, ball-handling skills, rebounding, passing, shooting fundamentals.

“Shooting is definitely a lost art, like rebounding,” he said. “We try to stay with the basics and keep it simple. If they master the fundamentals, everything else takes care of itself.”

Edit Image

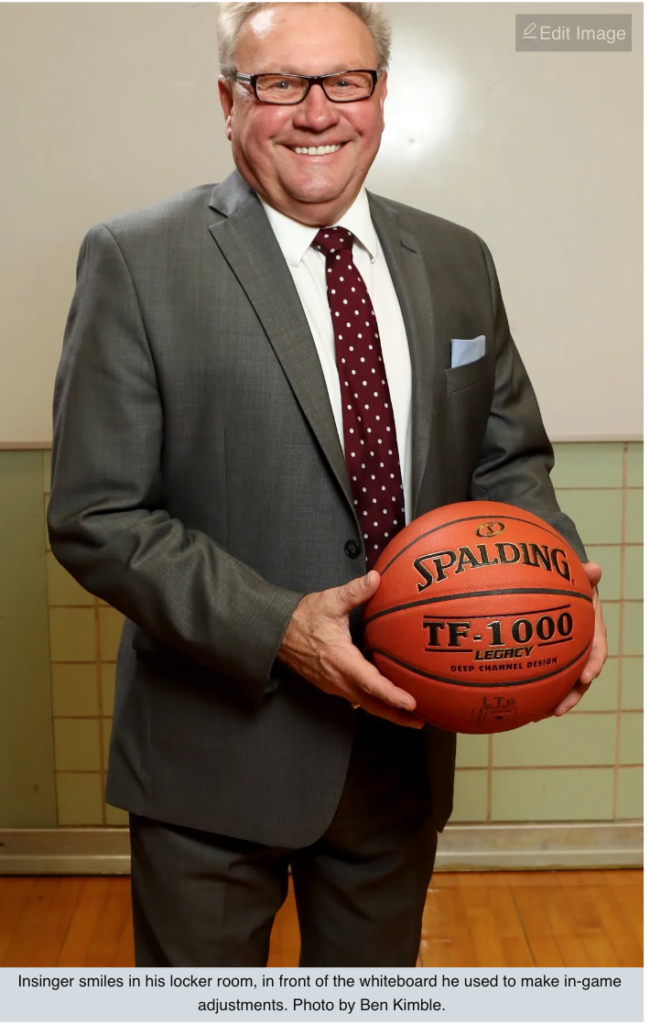

Insinger smiles in his locker room, in front of the whiteboard he used to make in-game adjustments. Photo by Ben Kimble.

Insinger taught physical education, coached basketball, and dabbled in businesses. A firm believer in having the coach inside the school building during the day, Insinger retired from teaching in 2009 only to assume the position of athletic director.

His teams pressed like Wooden’s. They ran the fast-break, like Wooden’s teams.

“We use the press to score in transition,” he said.

In Loyalock’s state playoff opening win over Palmerton this March, Blue Bomber coach Ken Termini said his team took an early punch. Loyalsock kept morphing its dynamic 1-2-2, 1-2-1-1 zone press to eliminate passing options. The passing lanes that looked open a minute ago now had a defender’s arms waiting to pounce.

“We got the margin down to like 12-15 points,” Termini said. “I was feeling like we had taken their best shot and we might be OK. But we hadn’t taken their best shot yet. They outscored us like 25-5 in the second quarter.”

Termini said the Lancers’ roster of strong football players blended well on the hardwood at Williamsport’s Magic Dome, obviously from years of playing together. That’s Insinger’s effect, starting players in second grade.

For 44 years he has run four weeks of basketball camp that services about 400 boys and girls each summer. Insinger benefits in wins down the road. With the proceeds he takes in, he buys uniforms, warmup shirts and sneakers for his boys.

He hosts one summer league and takes his players to compete in others, as well as a few tournaments.

“We will play in 70 games from March to September,” he said. “Every team I’ve had has been willing to run through a wall for me. Our goal is to go .500 in the summer. We play as many teams better than us that we can find.”

Trips to Harrisburg put the Lancers across from Carlisle, Cumberland Valley, Harrisburg High. All to prepare his smallish school district team to compete against the best in the winter.

“I used to say our goal at the start of every season was to get to Hershey,” he said. “I’m not sure that’s realistic anymore.”

More non-boundary teams appear every year–charter schools, private schools, and city schools that can draw from a huge territory.

After beating Palmerton by 32 in the first round of the state playoffs, Loyalsock drew District 12 Bishop McDevitt of Philadelphia. The Lancers lost by 26. McDevitt advanced to the state semifinals where they lost to eventual runner-up Trinity by seven.

He’s reached Chocolatetown, USA once. the 1993 Lancers met Duquesne in Hersheypark Arena, the place Wilt made famous by scoring 100 points in one game.

Loyalsock led by seven when Insinger’s point guard developed stomach cramps. Duquesne turned the advantage into a 70-60 victory in Class A. Duquesne’s Kevin Price would graduate with 2,635 career points before heading off to … Duquesne University.

As the dream of a return trip fades, Insinger has realigned his focus. He keeps 8 to 10 varsity players, hoping to get each in for most of the quarters during the regular season.

His up-tempo system continues to pump out 1,000-point scorers, including Gerald Ross, the star of this year’s team who finished with over 1,700 points. Ross was Loyalsock’s 16th player to hit the milestone.

Said Insinger, “I’ve been blessed to have great players in all 45 years.”

Randy Glunk (1987-1991) finished with exactly 2,000 career points.

PETE WHITE’S BUSINESS ACUMEN

Former Williamsport High coach Pete White, whose 1984 team won a state title with its four-second fast break, built an empire running basketball camps all summer at several sites. Albright College and Slippery Rock University were perhaps the two most prolific.

Organizing and staffing the camps has been a job unto itself, but White has given Pennsylvania players a place to face better and different competition beyond the AAU circuit. He turned his passion into profit.

Insinger’s riches have come through diversifying. He owns three diners, two personal care/assisted living centers, a Dairy Queen and a Rita’s Italian Ice stand. He also earns income from his various rental properties, including apartments he owns.

The former farmer still outworks daylight. Always, he allots time for his boys, the sons of Loyalsock. Basketball comes first, but his businesses still appear prominently on his ledger.

With age, he’s relinquished his grip on both.

“I have an assistant coach who does the X’s and O’s (for my basketball team),” he said. “I’m there basically to make the players better men.”

Current Indiana Pacer Alize Johnson, a Williamsport native, spent plenty of hours in Insinger’s gym even though he didn’t attend Loyalsock High.

“We’ve become great friends,” Ron said.

Insinger’s daughters now have sons of their own. You might see them running around the gym, performing ball-boy duties for grandpa. They’re almost old enough to play for him, which would be a blessing for them, and for Ron.