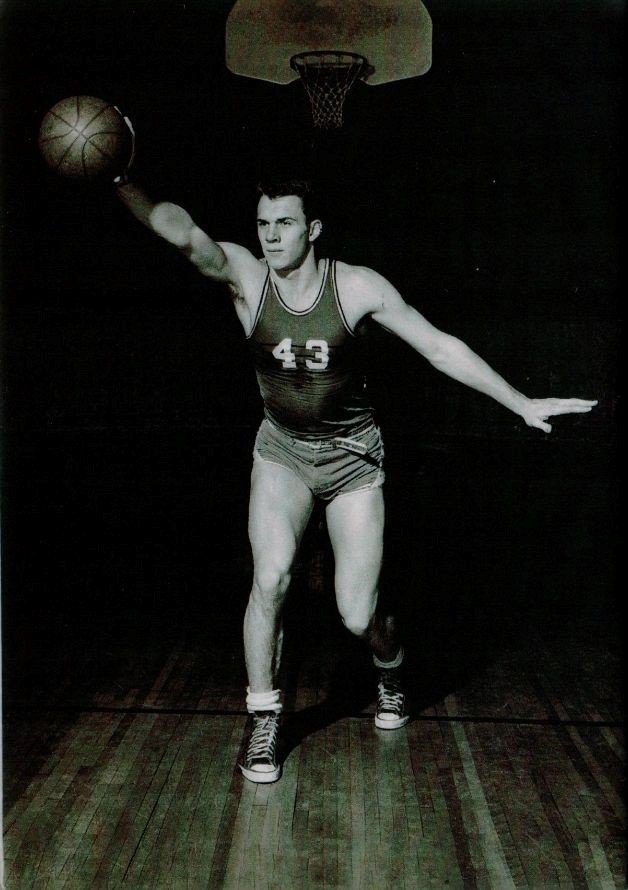

Len Chappell in his Portage uniform and Chuck Taylor sneakers. Photo courtesy of Joanne Chappell.

By BRADLEY A. HUEBNER

Lenny Chappell and Portage. The names are historically linked, intertwined like Larry Bird and French Lick. A huge star forever bonded to a tiny town.

As a Pennsylvania basketball coach and fan, I’d heard of Chappell from his association with Bethlehem product Billy Packer, Chappell’s Wake Forest University teammate in the late 1950s and early ’60s when Coach Bones McKinney, an ordained minister, helmed a team called the “Demon Deacons.”

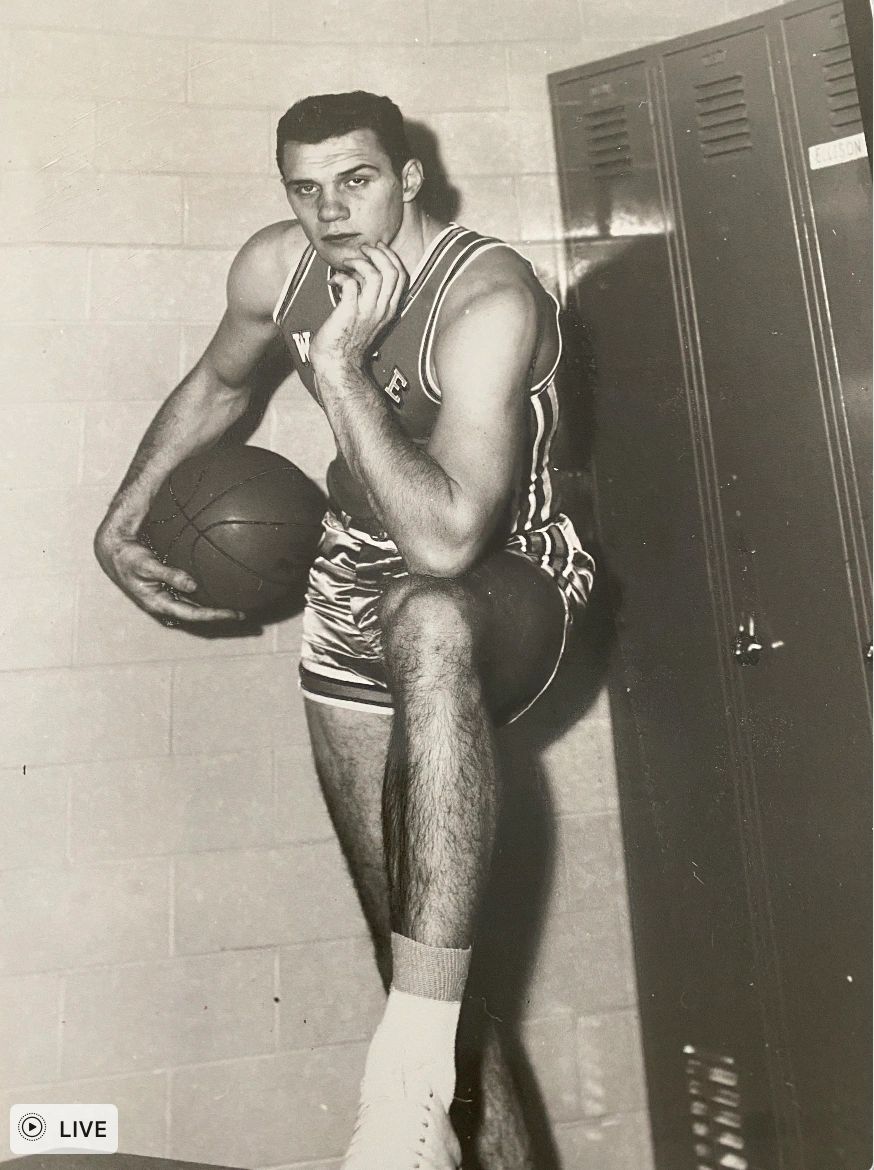

I knew two things about Chappell: he was built like a Roman statue decades before weightlifting was popularized, and he was uber-talented in basketball. Beyond that, I couldn’t tell you if he was white or black. A hook shot artist or a fast-break filler. His name resonated like a folk hero, a Mike Mulligan outperforming the steam shovel. Packer was his college sidekick, the point guard who did all the dribbling and passing and talking. Chappell–the 6-foot-8, 240-pound forward–handled the scoring and rebounding.

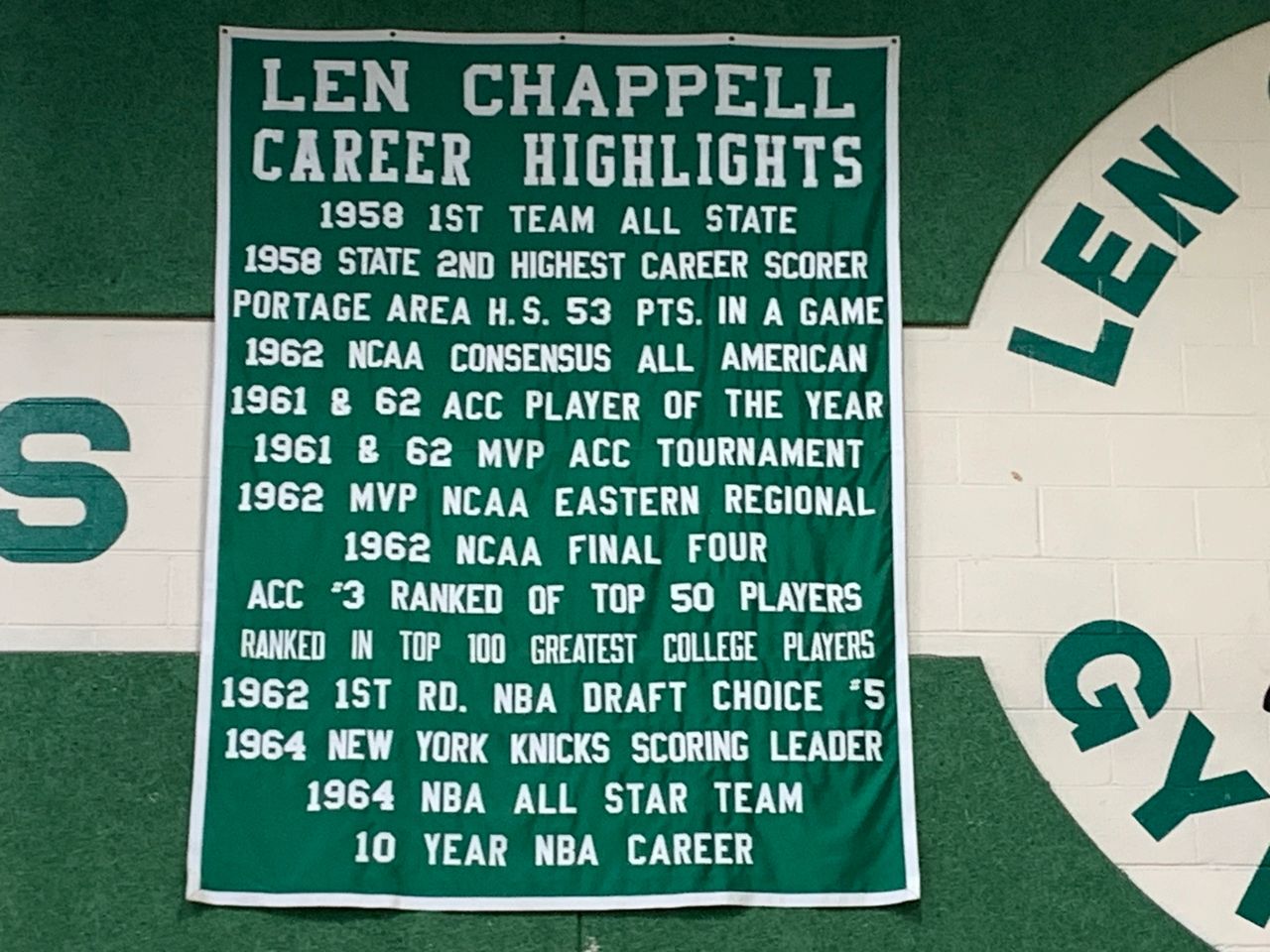

Last month I drove to Portage to research the late superstar. Chappell’s name adorns the gymnasium at his old high school, atop Mountain Avenue, the orange bricks of the school set behind a Mustang green outdoor basketball hoop in the middle of a parking lot once filled with cars on magical Friday nights.

Lenny was born to raise up his hometown, but never to stay there. He told friends that “these hands weren’t meant for mining coal,” something so many in Portage had done for a paycheck, for a lifetime. Chappell’s father died when he was a teenager, maturing Lenny into adulthood before his muscular body suggested he was one. The family lived next to their church, so the kids could lean on their faith when times got tough.

All throughout the mountain where they lived there were holes in the earth. Miners would descend into shafts, into darkness where they would chisel at anthracite clusters for their coveted resources. Not Lenny.

He discovered basketball during his junior high years, playing pickup games with locals in a barn which had a low roof that made high-arced jumpers impossible. One of seven siblings, Lenny didn’t come from a basketball family, so he came to the sport with a novice’s understanding. By his sophomore year, however, he was posting 40-point games, his exploits making the newspapers on the way to a legendary career total of 2,240 points.

As a senior, Chappell came within a basket-a-night of averaging 40 points per game long before the three-point line came into play. He nearly scored 1,000 points in his senior year alone. His three-year point total then ranked second only behind Ruthian legend Wilt Chamberlain of Overbrook High, who managed 12 more total points in his three seasons.

During the prestigious 1957 Christmas holiday tournament at Johnstown–the Great Flood town bankrolled by Bethlehem Steel–Chappell outscored Overbrook High star Wayne “The Cane” Hightower 19-11, but Overbrook won the game 60-47. That Overbrook squad–no longer featuring Wilt Chamberlain in the middle–also had future pros like Walt Hazzard and Wali Jones on its roster. Jones left impressed with Chappell.

“That was one big man,” said Wali Jones, who would go on to star at Villanova, about Chappell. “He always ran on his tippy toes.”

Overbrook won the tournament over Charleroi, another strong program led by future Arizona State player Ollie Payne. Hightower’s 36 points in the final clinched the MVP trophy for him.

In the consolation game, Portage led urban Chester High by eight at halftime before bowing 56-50. Chappell’s game-high 30 points were 24 more than any teammate and 13 more than any Chester Clipper. That against a Chester squad with future superstar Granny Lash.

Chappell was far more than a big fish in a country pond.

Before the Cambria County Johnstown Tournament, with Lenny playing in a small town in the middle of Pennsylvania’s woodlands, what recruiters would ever find Lenny Chappell?

In his autobiography, Wake Forest University coach Bones McKinney retells the famous anecdote of how he went to visit Duke basketball coach Harold Bradley, a friend of his, on Duke’s Durham campus. McKinney wandered into an office that contained a blackboard listing the names of 25 or so recruits Duke was chasing. From that board McKinney discovered the names “Chappell” and “Packer.” In time Bones would drive 11 1/2 hours one way to recruit Chappell. He made the 23-hour round trip a whopping seven times back when roads and vehicles were pocked-marked and rickety! He tapped into Mrs. Chappell’s Christian faith to land blue-chip Lenny. Packer, meanwhile, grew tired of waiting for Duke to offer him a scholarship, so he signed with Wake Forest so he could beat the Dookies when they played against each other in the Atlantic Coast Conference.

Chappell had to inform schools like North Carolina, Michigan, Michigan State, Duke, and many others that he was heading to Winston-Salem, N.C.

In Chappell’s final high school game, the Mustangs faced larger Altoona High in the District 6 semifinals before over 3,500 fans at Juniata College, the largest crowd to ever see a game there to that point. Chappell scored a pedestrian 16 points and snared 22 rebounds in a 14-point defeat. Formidable totals, but not the stuff of folklore.

Overbrook’s Wayne Hightower (Kansas recruit), Chester’s Jerry Foster (Drake), and Charleroi’s Ollie Payne (Arizona State) joined Chappell on the first-team all-state squad. All but Payne played professional basketball. Billy Packer of Bethlehem made second team all-state out of Bethlehem’s Liberty High School and would become the broadcasting voice of the Final Four.

All of this I pulled from research, or the ACC Channel’s series “The Tournament: A History of ACC Men’s Basketball.” Chappell’s brother Bill, who remains in Portage, said Lenny’s game blossomed when Bones sent him to the Catskill Mountains in New York over the summer to play against college stars and professionals.

“They couldn’t stop him all through high school,” Bill said, “but it wasn’t until they sent him to the Catskills that his game took off. He wasn’t real good at the foul line. They fouled him a lot. He graduated high school, and Bob and I and Lenny went to the Catskills. Up there he met the old coach from Kentucky. (Adolph) Rupp told him he could have a scholarship with him. West Virginia was strong with him, too. Bill Russell was up there at that time. Bones McKinney set that deal up for Lenny to go there.”

In addition to teaming up with Billy Packer at Wake, Chappell was also fraternity buddies with football running back Brian Piccolo, who led the nation in rushing and scoring in 1964. Piccolo would develop cancer and pass away in 1970. The famous movie “Brian’s Song” captures Piccolo’s life, all the way through the Chicago Bears where he would join the great Gale Sayers in the backfield.

At Wake Forest, Chappell came within 75 points of matching his Portage High career total, twice earning all-American honors and reaching the NCAA Final Four in 1962, Wake Forest’s only appearance. Not even Tim Duncan got them there. In the 1962 East Regional, the Demon Deacons defeated Wali Jones’s Villanova squad to reach the Final Four. Jones, that old Overbrook High foe, scored a game-high 25. Chappell (22) and Packer (18) combined for 40.

Chappell’s postseason production remained consistent, too, as he held the ACC Tournament scoring record for 44 years until a Dookie (J.J. Reddick) surpassed him. On game nights, opponents preferred to lure Chappell and his Herculean frame away from the painted area, but Lenny had a soft shooting touch outside, too, despite growing up shooting line drives under the low ceiling of a Portage barn.

He was twice named ACC Player of the Year and twice was hailed as tournament MVP.

Said John Barr, who became close with Lenny in Texas as Chappell rounded out his professional career in Dallas, ” He wanted to take that shot to win the ballgame.”

Chappell spent 10 seasons in the NBA and ABA, a successful journeyman who played for 10 teams professionally, averaging 9 points and five rebounds. He made the all-star team in 1963-64 with the Knicks when he averaged 17 points and nine rebounds per game. John Chappell said his father never made more than $50,000 in a season, but Lenny played long enough to secure his pension.

The NBA and ABA in their early years were nothing like the polished best selves that arrived in the late 1970s and 1980s. Fights and drug use permeated the leagues. One year Lenny’s coach with the ABA’s Dallas Chapparalles, Tom Nissalke, put a bounty on the head of the Pittsburgh Condors’ John Brisker, offering $500 to anybody who took a swipe at him. Lenny asked to start that game. He and Brisker lined up for the opening tap. The referee hoisted the ball into the air, Brisker jumped, and Lenny stayed on the ground. Then Lenny lunged at Brisker and punched him in the face, knocking him out.

Author Terry Pluto shared the story in his book Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association. It spoke to Lenny’s aggressiveness and fearlessness on the court, which belied his mild, humble persona of it.

Chappell took the lump sum from his pension and used it to start a sporting goods store in Wisconsin, which is run by his widow Joanne today.

“The lump sum was taken because at the time there was no organization representing retired players,” Joanne said, “and Lenny wanted to protect me.”

Basketball was partly responsible for introducing Joanne and Lenny.

“He was 35 and out of basketball. I met him in an old-timer’s basketball tournament,” remembers Lenny’s second wife. “I’m nine years younger than him. I’m looking at a banner that they had in the Charlotte Coliseum for the 50th anniversary of the ACC. He was a top 100 athlete. His college picture was there. I was just 11 years old when he was in college.”

Lenny and his first wife raised a daughter Kirsten, who competed in crew at the University of Wisconsin on her way to becoming a lawyer. Lenny and Joanne raised two boys. John (6-foot-10) and Jason (6-foot-9) sought the advice of their father as they developed their basketball careers, but Lenny wasn’t made for coaching any more than he was made for coal mining.

“He definitely got me and my brother started,” John remembers. “Our first experience was in YMCA leagues. He started out coaching us, but he didn’t really have the patience for coaching kids. That wasn’t really something he wanted to do. He had a little bit of a temper. He would get hot-headed. For the most part he was laid back and pretty calm, but he would get easily frustrated.”

The boys developed nonetheless, teaming up on a 26-0 Wisconsin state championship team at New Berlin West High. John then spent a year at Fork Union Military Academy in Virginia, Jason a year at Wooster Academy in Massachusetts. When it came time to choose a college, the boys dipped back into Lenny’s past.

John was recruited by Wake Forest coach Dave Odom and prepared to attend Lenny’s alma mater. When Odom became the coach at the University of South Carolina, John followed him there.

Jason signed with home-state Wisconsin and Bo Ryan, a former Pennsylvania prep star at Chester High, the school Portage High had lost to in the 1957 Johnstown Cambria County Tournament consolation game a few years before Ryan played for the Clippers. At Wisconsin, Jason played in 88 games, averaging three points and three rebounds.

“Jason liked to bang,” Bo Ryan said. “Contact he didn’t shy away from. Anytime in the Big 10 if you can get a big guy with a decent touch. … He had good post moves. Defensively and rebounding he contributed and started maybe his last two years. I’d have to go back through the archives. Jason did for us what we needed him to do, so that puts him in that really good category.”

Ryan remembers the Badgers’ team trip to Italy, when Lenny Chappell went along.

“He was a great parent because he never interfered,” Ryan joked. “It’s amazing when guys say, ‘You mean to tell me you never had a problem with a parent in 40 years of coaching?’ I actually only had one and that was at Sun Valley High School.”

Two years ago I was coaching high school basketball in Maryland. We played a game at a gym where a friend of mine had posted over 400 career wins as a head coach. In the hallway they hung a wooden plaque that was smaller than notebook paper, listing the coach’s accomplishments. No photo. No trophies next to it. None of the championship banners his teams had won.

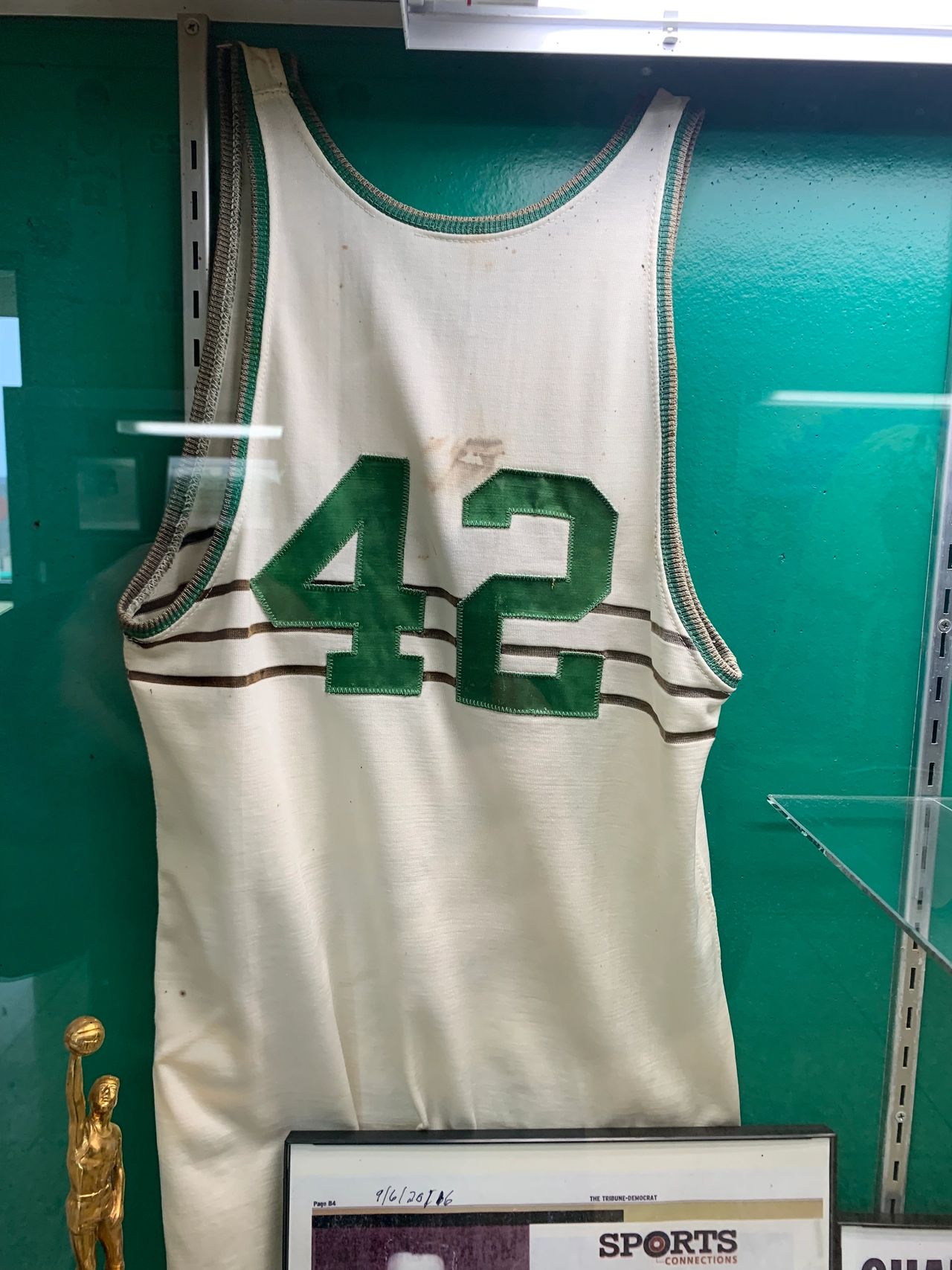

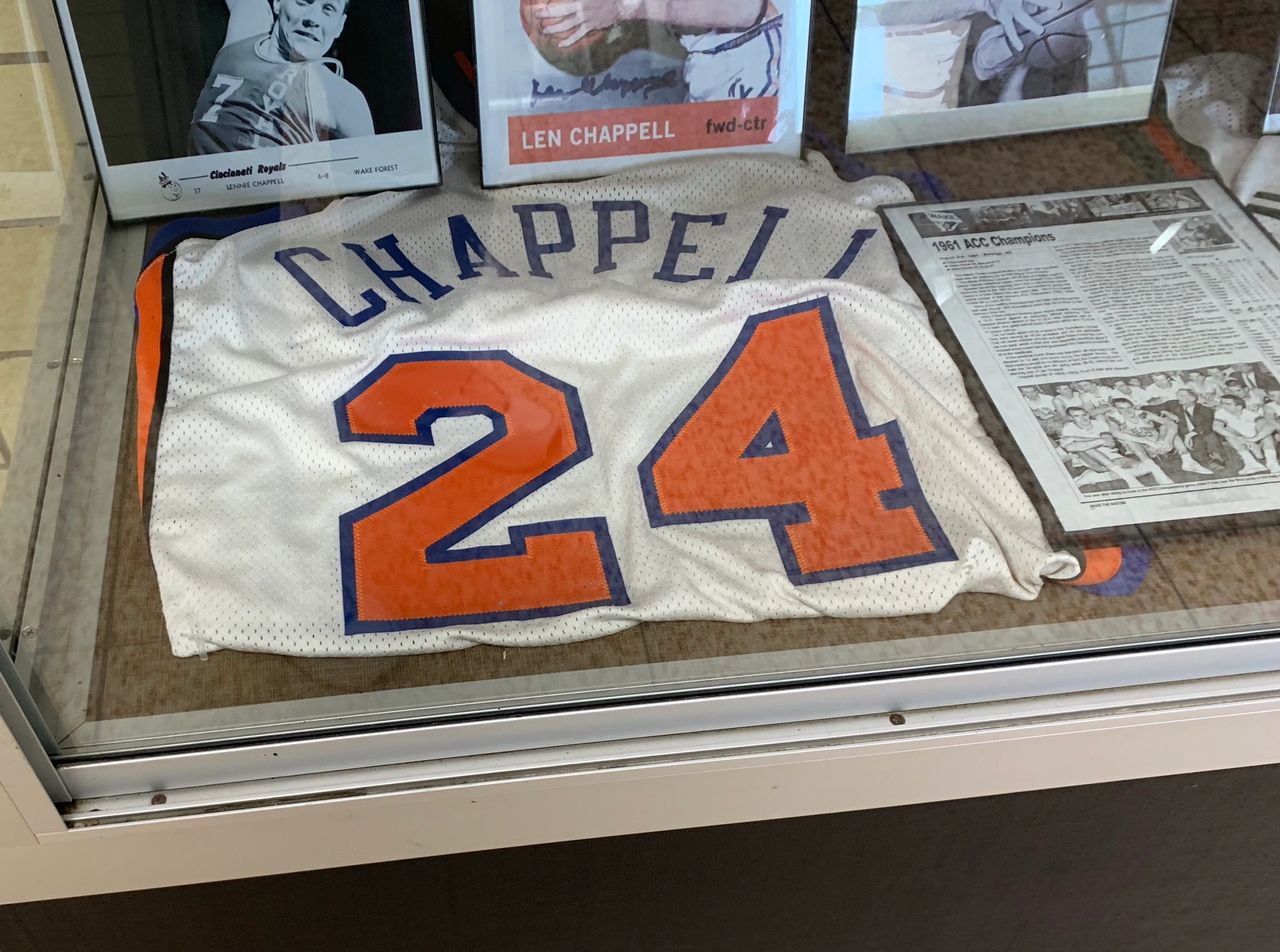

The athletic director had worked with that coach and made sure the coach was honored. But I always felt the coach deserved much more for his three decades of success. In 2023 I drove to Portage to see Lenny Chappell’s hometown and home gym. I found a trophy and memorabilia case befitting a legend. Finally! It included Lenny’s old home and away jerseys he had worn at Portage in a giant class showcase. A Knicks jersey. Plentiful newspaper clippings and photos and keepsakes.

“This is the best tribute to an alumnus that I’ve ever seen,” I told principal Jeremy Burkett.

“It’s a lot easier when you only have one or two or three main athletes to honor,” he said.

Portage, he said, is actually better known for success in football, a sport Lenny never played though I could envision him as a Chicago Bears defensive end had he pursued the sport.

In 2023, the Portage Mustangs basketball team turned out another stellar basketball season, 25-3 and three-peated as District 6 Class A champions.

Coach Travis Kargo was a native who came back to carry on the tradition. During the span he had three sons playing for him, he elevated the program to championship status. His middle child, Mason, was part of a senior class that went 95-15 over four years. Kargo has ignited a rebirth in Mustang basketball.

Though he recently turned 50, Coach Travis Kargo has already coached for 23 seasons and won 300 games. The glory years came with at two or three Kargos in the program: Coach Travis, Koby, Mason, and Trae. His wife Tonilyn spends her days running for Cambria County judge when she’s not supporting her family’s hoop dreams. This family accelerates in all respects. The team, too.

“We’re up-tempo on offense,” Coach Kargo said. “We like transition. Defensively we’re pretty much all man. This year we didn’t press as much. We were a little bigger.”

Kargo’s center was Luke Scarton, a 6-foot-6, 270-pound monster in the Chappelle mold. He’s going to play football at Loch Haven. Kargo also had 6-3 Bode Layo, whose uncle Brian had played for Portage before going on to play football at Marshall University.

For these diminishing once-robust coal towns to remain and thrive, they need prominent families to proliferate … and stick around town.

“It’s sort of like a throwback town,” explained Kargo, a special education teacher at the high school. “It’s small and getting smaller–56 in the graduating class this year. When I graduated there were 99 kids in 1991. My brother in 1987 had 119. When Lenny played it was closer to 150 or 170 back then. We had hotels, a Waldorf. It was a big mining town. They’re opening some mines up again, but it’s not like it was. Now it’s economically depressed overall. They used to call it Brain Drain. The kids would go to college, get degrees, and move away.”

The Kargo clan’s connection to town and basketball dates back to Lenny’s days. Travis’s father Ray was a contemporary of Lenny’s, but he played more street basketball than for the Mustangs before he entered coaching. Ray’s family owned a popular dance hall in town where teenagers would go after games.

“They called it ‘Big K’ back then for Kargo,” said Travis. “I was in the building when I was a kid. It was no longer the dance hall. More like a convenience store. We had a gas pump out front. It’s the front section of my grandmother’s house now. We still call it “The Store.'” Picture Arnold’s Restaurant in the old “Happy Days” sitcom, a gathering place for high school students to eat, shimmy and flirt. In small towns, that sense of community permeates daily life.

Go to any Portage playoff basketball game these days and you’ll see 2,000 fans screaming for a title. The school won its first state playoff game in 2015 (Chappell’s teams had fewer classifications, so they often lost to larger schools while chasing a district title).

It seems like forever that the Kargos have been either playing, coaching, or advising the cheerleaders in Portage. After playing basketball here, Travis went to Lebanon Valley College. He was in the same recruiting class as future All-American and LVC national champion Mike Rhoades (1995).

This week Rhoades was hired to coach men’s basketball at Penn State University. Since Travis only played one season at LVC, he didn’t get to experience the national title.

In the state playoffs, the current Mustangs often advance as far as the nearest catholic school opponent, like Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, who ended the Mustangs’ seasons during OLSH’s run of two unbeaten state titles and 74 straight victories. Two years ago they reached the state semifinals, Pennsylvania’s Final Four, in Class 2A. Last year they reached the quarterfinals. Kennedy Christian eliminated them.

All of the success in the modern age harkens back to Lenny Chappell’s days. On Friday nights in the winter it all happens inside Len Chappell Gymnasium.

“I get the folklore,” said Coach Kargo, “as a Portage person and as a coach and as my dad knowing him a little bit. When you look at how decorated Lenny is, it’s amazing to think he came from Portage.”

And it’s just as amazing, upon reflection, that the Kargos have stayed here.

Just when Joanne starts to think people won’t remember Lenny anymore, this happens: “The type of person Lenny was,” Joanne recalls, “I was on a cruise several years ago. He had passed away. If there was anybody from New York I’d open up the conversation and say, ‘Did you know my husband played for the Knicks?’ Two older guys there obviously from New York. One of the guys goes, ‘Who was it?’ Len Chappell. “You’re Mrs. Chappell? I’m talking to Mrs. Chappell? Your Mrs. Chappell?’ He’d be down at the Garden during the basketball games since his cousin worked there. Lenny was playing for the visiting team at the Garden. Whatever team Lenny was playing for that night beat the Knicks and the Knicks were really grumpy. Lenny’s locker room door was open and he walked in. Lenny took me around and introduced me to all the players like I was an old friend. He just had a fond place in his heart for Lenny, and the man on the cruise was absolutely thrilled to meet me.”

A QUICK STORY FROM AN OLD WAKE FOREST TEAMMATE

Lenny’s daughter Kirsten shared a story from one of her father’s former Demon Deacons teammates, which captures how Lenny Chappell was both physically strong and yet gentle at the same time:

“I never saw him angry except freshman year when one of the guys in our suite came in late one night drunk and messed up the bathroom in the hall. And your dear gentle giant Lenny literally picked him up and held him against the wall and said, “Don’t you ever do that again! I ran into that classmate at our 50th reunion and he recalled us that event — he is an attorney now doing well, so I guess he learned his lesson! As for (this season’s college) basketball, I’m glad that it’s over. I loved watching the ladies play; the men have gotten too physical.”